Film review: How to attack the Legion of Boom

After spending more time than any of us would like to admit discussing balls, it's time to move on to Seattle and the incredible football game Sunday figures to provide. To familiarize myself with the Seahawks, I went back and watched the film of three Hawks games: their dramatic NFC championship game win over the Packers, their Week 3 overtime triumph over Denver and the Patriots upset loss to the (at the time) upstart Seahawks in 2012. After discussing the Hawks zone-heavy scheme and Russell Wilson's unique mobility, I'm shifting gears and attacking the toughest question Bill Belichick's Patriots face on Sunday: how the heck do you attack Seattle's notorious "Legion of Boom"?

Understanding the Cover 3

Given the complexities of modern day NFL offenses, it's remarkable that Seattle's defensive takeover of the league has been built almost exclusively around one of football's most simplistic coverage schemes. While the Hawks corners are known for their physical press coverage, they typically do so within the confines of Pete Carroll's Cover 3 zone.

In this case, the Pats send Rob Gronkowski on a seam, hoping to clear out space underneath for Wes Welker. The plan works for a second, as Welker is open, but Brady is a split-second late pulling the trigger. By then, Welker's route has taken him into the zone of linebacker Bobby Wagner, forcing Brady to throw behind Welker. Welker is walloped by Wagner a split second after the pass deflects off his hands, and Earl Thomas is able to come up from his deep zone and pick it off to deny the Pats a scoring chance.

Of course, there are plenty of variables worked into this basic defensive philosophy. Here, the nickel corner (back in 2012, that was Marcus Trufant) drops into zone covering the right flat. The Hawks still do that, but they often trust their nickel corner (now Jeremy Lane) in man coverage, while the rest of the secondary breaks into zone. In that case, the basic cover 3 principles remain, with the underneath defenders (typically two linebackers and Kam Chancelor) split the field into three zones.

For example, take this week three play against Denver. Slot corner Marcus Burley has Wes Welker one-on-one in the slot, while the linebackers and Chancelor split the middle into three distinct zones. Manning recognizes man coverage and goes after Burley, but Burley and zone defender Bobby Wagner play it well and limit Welker to a gain of just three yards.

Playing this much zone is a dangerous game for most teams in this pass-happy NFL, but Seattle has excelled with it largely due to excellent talent that fits the scheme well. While the legion of boom have gotten much of the attention, the scheme wouldn't work without the range of linebackers like Wagner, KJ Wright and Malcolm Smith. They also benefit from an excellent pass rush that often limits the time opposing quarterbacks have to find any holes in the zone.

Every zone has it's holes

It often doesn't seem like it watching the Seahawks play, but even a team as well-versed with their scheme as Seattle will have holes when playing zone. The key is using offensive personnel and formations to create space, something Tom Brady and the Patriots offense excel at.

One way to do that is to bunch receivers up in the formation, attempting to create confusion and force a defender to chose between defending two players. Denver did that frequently in their Week 3 game, including on this third down play.

The play is pretty simple: the inside receiver on the bunch runs a vertical route, clearing out the outside corners and occupying Thomas deep. Meanwhile, the outside receiver on the bunch runs a basic in cut, looking for a hole in the middle of the zone.

As you can see, Seattle initially has the play defended perfectly. The outside corners are in great position to handle those go routes up the field, and both underneath receivers are accounted for. However, problems start when Denver running back Montee Ball leaks out into the left flat on a delayed route. Linebacker K.J. Wright sees Ball and fires out aggressively to take away Manning's checkdown, theoretically passing off his zone to Wagner. This temporarily leaves Julius Thomas open over the middle, and Manning finds him before Wagner can slide over and take away that space.

Designed to take away the deep ball, Seattle's zones can leave them vulnerable underneath. Here's former Hawks quarterback Matt Hasselbeck summing up the defensive philosophy in it's most basic form:

For instance, take a look at this fourth quarter play from that game. Conceptually, the play is almost identical to the one outlined above: a double bunch formation, go routes from the inside receivers to occupy the corners and Thomas, and inside routes from the two outside receivers.

However, a small adjustment to the depth of said routes can make all the difference in the world against a zone. By shortening Welker's route and adding depth to that of Julius Thomas, Denver ensures that Welker will have space underneath in front of the zone drops of Seattle's linebackers. Manning hits him quickly, and the inside routes of Julius Thomas and Montee Ball are designed to put them in perfect place to immediately throw blocks for him. The result of the play is a 13 yard drive starter, and Denver runs the same play from the opposite side for 15 yards just four snaps later.

Stuff like that is New England's bread and butter, as I wrote two weeks ago about the two-man game New England used with Gronkowski/Edelman to free up their slot receiver against Indianapolis. The Hawks will gladly give up short passes, trusting their athletic defense to quickly make tackles, limit yards after the catch, and force their opponent to have perfect execution play after play after play to beat them. Most teams don't have the personnel or brainpower to do so. New England just might, although it will certainly take their best football on Sunday.

The Earl Thomas factor

Another vulnerable spot in the Cover 3 zones can be the space between the linebackers and deep safety, but Earl Thomas's rare combination of range and instincts makes that a very dangerous game to play. Injured shoulder or not, Thomas is an Ed Reed-type playmaker who must be accounted for on every snap.

Thomas's range is really what makes him special, as it enables Thomas to get to balls most safeties simply aren't able to reach. Whatever space you might think you have against him will disapear in a hurry. Despite his small size, Thomas is absolutely fearless; once he makes a read, he is flying to the football like a tazmanian devil in shoulder pads. Underestimate his range and risk him picking the ball off and returning it the other way for six.

Brady nearly learned that the hard way back in that 2012 game on this red zone play. The play starts out promising, as Brady sees he has Gronk in man coverage against linebacker K.J. Wright. Wright is an excellent coverage LB, but Brady will go to Gronk one-on-one against anyone. Against a linebacker, the read is a no-brainer.

Unfortunately for Brady, Thomas has done his homework. He recognizes the matchup, realizes Brady will go to it and aggressively jumps Gronk's out route. The Pats are very fortunate Thomas is unable to cleanly corral Brady's pass, as it's a likely pick six if he does.

That speed and aggression is what makes Thomas a great player, but it can also be targetted as a weakness in the right situation. A major part of the mental battle on the field Sunday will be Brady's attempts to use his eyes to draw Thomas away from the matchups he likes. If the Pats can get some semblance of a running game going, play action could be another way to take Thomas's aggression and turn it on itself.

As dangerous as Thomas's range does make him, it occasionally leads him to make gambles that even he can't recover from. Brady caught him once in that 2012 game, as Thomas, likely underestimating the speed of Wes Welker, waits too long to get into his backpedal as Welker enters his deep zone. Welker runs right past him, and Brady makes a perfect throw for a 46 yard touchdown.

However, the plays Thomas gives up are minimal, especially compared to those he disrupts. The big question mark becomes whether his recently separated shoulder will affect his reckless style of play. Thomas has already acknowledged to the press that he'll have to adjust his tackling technique due to the injury, and the Pats ball carriers will certainly look to finish their runs with physicality against him. Even for a stud like Thomas, tackling a beast like Gronk or LeGarrette Blount is a tall task with a shoulder that's a good hit away from popping out.

What about Sherm?

Of course, any piece on the Legion of Boom would be incomplete without mention of the face of the franchise; outspoken star corner Richard Sherman. Sherman has a pregnant fiance due any day now along with his sprained elbow, but you can bet your bottom dollar that he'll be out there Sunday in his usual spot at left corner.

Will the Patriots test Sherman? I can't see them simply sacrificing his side of the field to avoid him, as some teams have done against the Hawks, but Brady will surely be careful whenever looking his way. Sherman's receiver-like ball skills make him a major threat to pick off any 50/50 ball thrown his way. Aaron Rodgers was merely the most recent quarterback to learn that the hard way, as Sherman ended the Packers first possession of the NFC championship game with a toe-tapping pick in the end zone. Rodgers wouldn't target him the rest of the game.

Attacking Sherman down the field likely isn't worth the risk, but the loudmouth corner could be more vulnerable against the quickness of slot-types Julian Edelman and Danny Amendola. Sherman, who generally covers big downfield receivers, could find it more difficult to get a jam on the Pats smaller, shiftier receivers, and the short routes they typically run are much harder for a corner to get his mitts on.

Of course, the fact that Sherman rarely moves from his customary left corner spot will make it easier for the Pats to dictate their matchups against him. One trick the Packers used was splitting tight end Richard Rodgers out wide to his side, forcing Sherman to come inside and defend the slot. The Pats could do that with Michael Hoomanawanui, forcing Sherman to stay with a deft route runner like Edelman without the assistance of the sideline.

Of course, if Sherman's injured elbow takes away his ability to play physical and jam receivers, it could be a different ball game. The Pats will surely test that shoulder out early, perhaps by lining the physical Brandon LaFell across from him on running plays. Sherman is one of the best corners in the league against the run, but asking him to fight off LaFell play after play is a tall task.

No matter what, it's a safe bet that Brady will target right corner Byron Maxwell and slot man Jeremy Lane far more often than Sherman. That's nothing new for either player, both of whom have held up exceptionally well despite seeing plenty of targets from quarterbacks wary of looking Sherman's way. Aaron Rodgers did complete 5 of his 7 passes Maxwell's way for 72 yards (14.4 ypc) in the NFC championship game, but Maxwell came up with an interception that game. Meanwhile, Lane has done an excellent job of making tackles and limiting yards after the catch from his slot position: for the entire year (including postseason), he's allowed a low average of just 8 yards per reception.

Understanding the Cover 3

Given the complexities of modern day NFL offenses, it's remarkable that Seattle's defensive takeover of the league has been built almost exclusively around one of football's most simplistic coverage schemes. While the Hawks corners are known for their physical press coverage, they typically do so within the confines of Pete Carroll's Cover 3 zone.

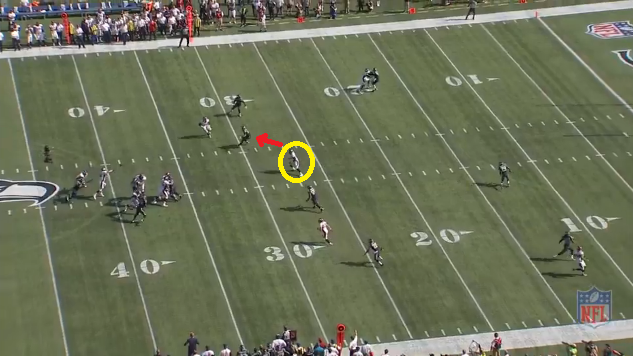

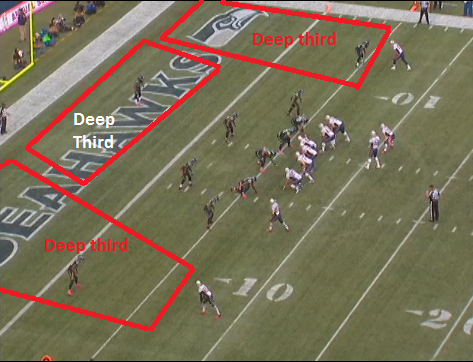

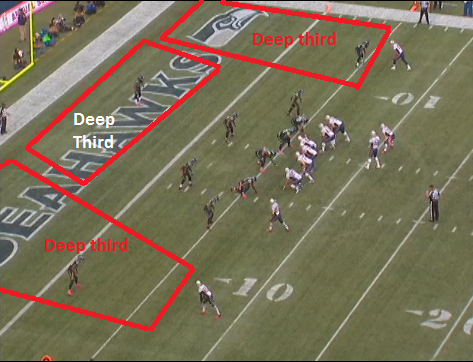

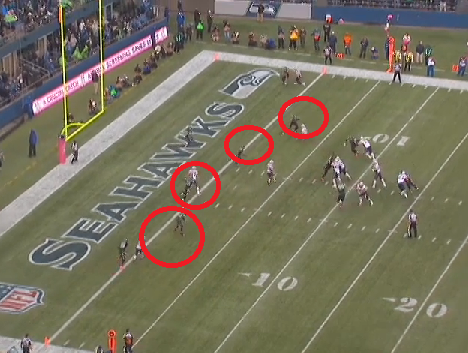

This play, a fourth quarter Brady interception from the 2012 game, is a good example of how the Cover 3 works. As you can see, the scheme splits the field into three deep zones, with the outside corners responsible for the sidelines and a safety (usually Earl Thomas) patrolling the middle of the field.

With the deep zones of the field covered, the linebackers (and on this play, slot corner) are free to drop into underneath zones. On this play, with less space to defend in the red zone, the defense splits the into four underneath zones. In this case, the goal is to congest the middle of the field, making Brady choose between taking a shot against tight coverage on the sidelines or forcing a dangerous ball over the middle.

In this case, the Pats send Rob Gronkowski on a seam, hoping to clear out space underneath for Wes Welker. The plan works for a second, as Welker is open, but Brady is a split-second late pulling the trigger. By then, Welker's route has taken him into the zone of linebacker Bobby Wagner, forcing Brady to throw behind Welker. Welker is walloped by Wagner a split second after the pass deflects off his hands, and Earl Thomas is able to come up from his deep zone and pick it off to deny the Pats a scoring chance.

Of course, there are plenty of variables worked into this basic defensive philosophy. Here, the nickel corner (back in 2012, that was Marcus Trufant) drops into zone covering the right flat. The Hawks still do that, but they often trust their nickel corner (now Jeremy Lane) in man coverage, while the rest of the secondary breaks into zone. In that case, the basic cover 3 principles remain, with the underneath defenders (typically two linebackers and Kam Chancelor) split the field into three zones.

For example, take this week three play against Denver. Slot corner Marcus Burley has Wes Welker one-on-one in the slot, while the linebackers and Chancelor split the middle into three distinct zones. Manning recognizes man coverage and goes after Burley, but Burley and zone defender Bobby Wagner play it well and limit Welker to a gain of just three yards.

Every zone has it's holes

It often doesn't seem like it watching the Seahawks play, but even a team as well-versed with their scheme as Seattle will have holes when playing zone. The key is using offensive personnel and formations to create space, something Tom Brady and the Patriots offense excel at.

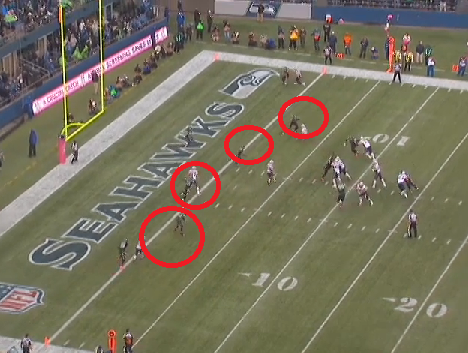

One way to do that is to bunch receivers up in the formation, attempting to create confusion and force a defender to chose between defending two players. Denver did that frequently in their Week 3 game, including on this third down play.

The play is pretty simple: the inside receiver on the bunch runs a vertical route, clearing out the outside corners and occupying Thomas deep. Meanwhile, the outside receiver on the bunch runs a basic in cut, looking for a hole in the middle of the zone.

As you can see, Seattle initially has the play defended perfectly. The outside corners are in great position to handle those go routes up the field, and both underneath receivers are accounted for. However, problems start when Denver running back Montee Ball leaks out into the left flat on a delayed route. Linebacker K.J. Wright sees Ball and fires out aggressively to take away Manning's checkdown, theoretically passing off his zone to Wagner. This temporarily leaves Julius Thomas open over the middle, and Manning finds him before Wagner can slide over and take away that space.

Designed to take away the deep ball, Seattle's zones can leave them vulnerable underneath. Here's former Hawks quarterback Matt Hasselbeck summing up the defensive philosophy in it's most basic form:

"Really, that's what the [Seahawks] want to do - they want to bail, they want to give you flat routes all day, and just say hey, we dare you to have the patience to just dink and dunk it down the field."The Patriots, of course, run an offense that is more or less designed to dink and dunk it down the field, and Denver's furious fourth quarter comeback against these Seahawks could provide some clues as to how to take advantage of that and create space.

However, a small adjustment to the depth of said routes can make all the difference in the world against a zone. By shortening Welker's route and adding depth to that of Julius Thomas, Denver ensures that Welker will have space underneath in front of the zone drops of Seattle's linebackers. Manning hits him quickly, and the inside routes of Julius Thomas and Montee Ball are designed to put them in perfect place to immediately throw blocks for him. The result of the play is a 13 yard drive starter, and Denver runs the same play from the opposite side for 15 yards just four snaps later.

Stuff like that is New England's bread and butter, as I wrote two weeks ago about the two-man game New England used with Gronkowski/Edelman to free up their slot receiver against Indianapolis. The Hawks will gladly give up short passes, trusting their athletic defense to quickly make tackles, limit yards after the catch, and force their opponent to have perfect execution play after play after play to beat them. Most teams don't have the personnel or brainpower to do so. New England just might, although it will certainly take their best football on Sunday.

The Earl Thomas factor

Another vulnerable spot in the Cover 3 zones can be the space between the linebackers and deep safety, but Earl Thomas's rare combination of range and instincts makes that a very dangerous game to play. Injured shoulder or not, Thomas is an Ed Reed-type playmaker who must be accounted for on every snap.

Thomas's range is really what makes him special, as it enables Thomas to get to balls most safeties simply aren't able to reach. Whatever space you might think you have against him will disapear in a hurry. Despite his small size, Thomas is absolutely fearless; once he makes a read, he is flying to the football like a tazmanian devil in shoulder pads. Underestimate his range and risk him picking the ball off and returning it the other way for six.

Brady nearly learned that the hard way back in that 2012 game on this red zone play. The play starts out promising, as Brady sees he has Gronk in man coverage against linebacker K.J. Wright. Wright is an excellent coverage LB, but Brady will go to Gronk one-on-one against anyone. Against a linebacker, the read is a no-brainer.

Unfortunately for Brady, Thomas has done his homework. He recognizes the matchup, realizes Brady will go to it and aggressively jumps Gronk's out route. The Pats are very fortunate Thomas is unable to cleanly corral Brady's pass, as it's a likely pick six if he does.

That speed and aggression is what makes Thomas a great player, but it can also be targetted as a weakness in the right situation. A major part of the mental battle on the field Sunday will be Brady's attempts to use his eyes to draw Thomas away from the matchups he likes. If the Pats can get some semblance of a running game going, play action could be another way to take Thomas's aggression and turn it on itself.

As dangerous as Thomas's range does make him, it occasionally leads him to make gambles that even he can't recover from. Brady caught him once in that 2012 game, as Thomas, likely underestimating the speed of Wes Welker, waits too long to get into his backpedal as Welker enters his deep zone. Welker runs right past him, and Brady makes a perfect throw for a 46 yard touchdown.

However, the plays Thomas gives up are minimal, especially compared to those he disrupts. The big question mark becomes whether his recently separated shoulder will affect his reckless style of play. Thomas has already acknowledged to the press that he'll have to adjust his tackling technique due to the injury, and the Pats ball carriers will certainly look to finish their runs with physicality against him. Even for a stud like Thomas, tackling a beast like Gronk or LeGarrette Blount is a tall task with a shoulder that's a good hit away from popping out.

What about Sherm?

Of course, any piece on the Legion of Boom would be incomplete without mention of the face of the franchise; outspoken star corner Richard Sherman. Sherman has a pregnant fiance due any day now along with his sprained elbow, but you can bet your bottom dollar that he'll be out there Sunday in his usual spot at left corner.

Will the Patriots test Sherman? I can't see them simply sacrificing his side of the field to avoid him, as some teams have done against the Hawks, but Brady will surely be careful whenever looking his way. Sherman's receiver-like ball skills make him a major threat to pick off any 50/50 ball thrown his way. Aaron Rodgers was merely the most recent quarterback to learn that the hard way, as Sherman ended the Packers first possession of the NFC championship game with a toe-tapping pick in the end zone. Rodgers wouldn't target him the rest of the game.

Attacking Sherman down the field likely isn't worth the risk, but the loudmouth corner could be more vulnerable against the quickness of slot-types Julian Edelman and Danny Amendola. Sherman, who generally covers big downfield receivers, could find it more difficult to get a jam on the Pats smaller, shiftier receivers, and the short routes they typically run are much harder for a corner to get his mitts on.

Of course, the fact that Sherman rarely moves from his customary left corner spot will make it easier for the Pats to dictate their matchups against him. One trick the Packers used was splitting tight end Richard Rodgers out wide to his side, forcing Sherman to come inside and defend the slot. The Pats could do that with Michael Hoomanawanui, forcing Sherman to stay with a deft route runner like Edelman without the assistance of the sideline.

Of course, if Sherman's injured elbow takes away his ability to play physical and jam receivers, it could be a different ball game. The Pats will surely test that shoulder out early, perhaps by lining the physical Brandon LaFell across from him on running plays. Sherman is one of the best corners in the league against the run, but asking him to fight off LaFell play after play is a tall task.

No matter what, it's a safe bet that Brady will target right corner Byron Maxwell and slot man Jeremy Lane far more often than Sherman. That's nothing new for either player, both of whom have held up exceptionally well despite seeing plenty of targets from quarterbacks wary of looking Sherman's way. Aaron Rodgers did complete 5 of his 7 passes Maxwell's way for 72 yards (14.4 ypc) in the NFC championship game, but Maxwell came up with an interception that game. Meanwhile, Lane has done an excellent job of making tackles and limiting yards after the catch from his slot position: for the entire year (including postseason), he's allowed a low average of just 8 yards per reception.