Check the Film: How Brady carved up the Steelers zone coverage (again)

|

| Brady and the Patriots rolled offensively against the Steelers. Same as it ever was! AP Photo/Steven Senne |

Sunday's results shouldn't have been surprising to anyone whose been paying attention for the last 15 years. Tom Brady has spent his entire career dismantling the Steelers defense at every opportunity, including when said defense was a championship-level unit. Simply put, the Steelers have largely run the same defensive scheme for the entirety of Brady's career: a 3-4 front that uses a variety of zone coverages to enable it to send disguised blitzers from unpredictable spots. Implemented by legendary former defensive coordinator Dick LeBeau, this scheme has generally worked for Pittsburgh, as they fielded one of the league's stingiest defenses for much of the 2000's en route to three Super Bowl appearances and two championships.

However, Brady figured out where the soft spots are in Pittsburgh's zones well over a decade ago. In general, you don't stand a chance if Brady has your coverage figured out before the snap. Watching Brady play against the Steelers on Sunday, it appeared that he knew the ins and outs of their coverage schemes almost as well as he knew his own offense. Actually, it appeared he knew their defense better than some of their defenders, who were frequently found pointing the finger at each other or throwing their arms up in exasperation after big Patriots plays.

One beautiful example of this came on the Patriots third possession. On first and 10, the Patriots come out in a personnel grouping and formation that screams run. James Develin joins LeGarrette Blount in the backfield, with tight end Martellus Bennett in a three point stance on the line next two the dominant run blocking duo of Marcus Cannon and Shaq Mason. The Steelers react accordingly with their base defense; as you can see, they have nine players in the box if you count slot defender Sean Davis.

|

| The Steelers packed the box in response to this run formation |

Next the Patriots motion Julian Edelman across the formation to the right slot. This does little to prevent the defense from thinking run. They are already bracing for a run to the right side, behind the trio of Mason, Cannon and Bennett, and the Pats will commonly run to Edelman's side to take advantage of his tenacious blocking. What the motion does do is force the defense to react, giving Brady precious clues to their intentions. In this case, no one follows the motion across the formation; instead left corner Ross Cockrell, previously without a receiver to his side, takes a step outside to match Edelman. The only other change comes from Davis, who is now unneeded on the defensive right side with only Hogan left there. Davis rotates back to a free safety position, with previous free safety Mike Mitchell coming down into the box to give the Steelers an extra run defender/potential blitzer on the presumed play side.

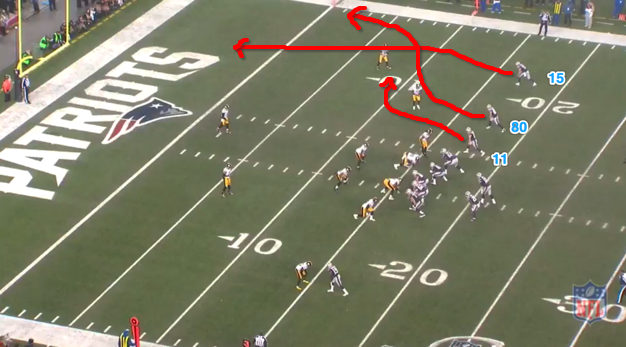

That's when the Patriots make their move. On an audible by Brady, Blount and Develin motion from out of the backfield to split wide on either side of the formation. Likewise, Bennett motions from the line to the slot, with Edelman moving even further inside. As a result, the defense is immediately in a conundrum. Mitchell is forced to scramble from the box back to a deep safety position alongside Davis. Trapped within the confines of their zone scheme, they have their corners lined up across from Develin and Blount, the Patriots two least threatening passing targets. The Patriots also have clear mismatches for their three inside receivers, as outside linebackers James Harrison and Bud Dupree are lined up across from Hogan and Bennett respectively. No one is even lined up directly across from Edelman, the closest coverage defender to him is hulking linebacker Lawrence Timmons.

|

| The Steelers are immediately put in several matchup predicaments after this Patriots motion |

The Patriots compound the Steelers already apparent problems with both an excellent play design and by snapping the ball before they've fully processed what just happened. Both Develin and Blount run simple hitch routes, designed merely to occupy their coverage defender for a few seconds. Meanwhile, Bennett and Hogan run vertical go routes, while Edelman runs a quick out. Edelman's out against a linebacker in zone is a nice safety valve for Brady (and one the defense to consider, but the real threat of the play is the vertical routes. With each player having an obvious speed mismatch initially, there's tremendous stress on the safeties to pick up the vertical routes before Brady can exploit them.

|

| Davis (#28) is scrambling to communicate before the snap and out of position against Hogan's go route |

As you can see from this snap shot, taken about a split second before the ball is snapped, Davis is still frantically communicating with fellow safety Mitchell and is in no position to prevent an easy completion down the seam to Hogan. Brady recognizes this, takes a three-step drop and immediately releases the ball for the easiest 26 yard completion you'll ever see. It's a perfect example of how the Patriots coaching, aided by practically having a coach on the field in Brady, often wins plays for them before the ball is even snapped.

Hogan would go on to cap that drive with the first of his two receiving touchdowns, on yet another example of how to beat zone coverage. On this third down play, the Patriots have nearly an identical alignment with three play-side receivers. This time, they are all actual receivers, with Hogan lined up outside, Danny Amendola in the slot and Edelman further inside.

|

| Hogan and Amendola "flood" left corner Ross Cockrell's zone here |

As you can see, this play is designed to stress the coverage by sending multiple routes through the same area of the field. It's a concept called "flooding the zone" and one the Patriots used repeatedly with success in this game. In this case, outside corner Cockrell begins the play on Hogan, who runs straight up the field. However, Amendola's wheel route puts him in a conundrum. As the outside corner, Cockrell is presumably responsible for anything vertical down his left sideline (aka Amendola's route). He recognizes the route combination and releases Hogan to pick up Amendola, presuming that Hogan's in-cutting post route will take him into the zone of a deep safety.

|

| Cockrell is forced to pick his poison here |

Unfortunately for Cockrell, that safety (veteran Robert Golden, #21) has his eyes on Edelman and never notices Hogan breaking free. In fact, Golden continues to fixate on Edelman and neglect Hogan in spite of slot corner William Gay picking up Edelman's route. As a result, Hogan is wide open long enough for Brady to move out of the pocket and reset his feet before finding him for the score.

|

| Golden's lack of awareness allows Hogan to run free into the end zone |

While Edelman's quickness underneath was often used as a decoy to distract from vertical routes developing downfield, the opposite was also true on a number of occasions. That was the case on the Pats second play from scrimmage, a 41 yard catch and run from Edelman that put the Pats immediately in scoring range. On this play, the Patriots went with an empty spread formation, deploying four receivers and excellent pass catching back Dion Lewis. The Steelers don't even have anyone lined up across from Danny Amendola (offense's left slot), which all buts eliminates man coverage as a possibility. Zone is almost a certainty, and the positioning of their two safeties (Mitchell, #23 and Davis, #28) at the snap suggests Cover 2, in which those safeties would each be responsible for a deep half of the field, with a linebacker (Lawrence Timmons, #94) dropping straight back to cover anything vertical up the middle.

|

| Deep responsibilities of a typical Cover 2 |

Brady knows this and, once again, dials up a play to take advantage. As you can see, both playside receivers (Mitchell, #19 and Amendola, #80) push their routes vertically up the field. That occupies the playside corner (rookie Artie Burns, #25) and the deep safety Mitchell, who is forced by scheme to give far too much cushion to Amendola. That cushion means that Amendola is initially open for a what would have been a solid gain, but his route is really designed to open up the underneath zone for Edelman, who is coming that way on a crossing route from the backside. Edelman makes his in-cut right behind zone defender Bud Dupree but underneath middle linebacker Timmons, who as predicted is dropping as the third deep defender in the Cover 2.

|

| This play is designed to create space underneath for Edelman to come free on a crossing route |

At the start of the play, the Steelers are already in trouble. The cushion Mitchell is forced to leave as a deep safety seems to confuse Burns (#25), who leaves Mitchell late to try to pick up Amendola. Regardless both defenders are out of position to pick up Edelman, who gets the ball wide open with a full head of steam and plenty of space, a terrifying situation for a defense that now has to bring the notoriously slippery receiver down. Jules takes full advantage, breaking a tackle attempt by Burns before making Timmons miss in the open field during a massive run after the catch.

|

| Both Burns and Mike Mitchell react to Amendola, leaving Malcolm Mitchell and Edelman wide open |

These are just a handful of the seemingly countless examples I could have picked from this game, as Brady did pretty much whatever he wanted all game against a Steelers defense that schematically never had a chance. The question becomes whether he can do the same against a Falcons defense that also likes to stick with zone coverages. My guess is that it certainly won't be as easy. The Steelers schematic disadvantages weren't helped by glaring execution lapses, highlighted in the examples above by Blanton's lack of awareness on the Hogan touchdown. The Falcons also have a lot more speed on defense than the Steelers, which should help to close the opens faster than the Steelers were able to muster.

However, I'd still expect a good day at the office for Brady. The Falcons generally stick with the Cover 3 zones head coach Dan Quinn brought over for Seattle. Cover 3 is designed to prevent the big play, with the boundary corners and deep free safety each responsible for one "deep third" of the field. However, it can be suspect against the quick hitting, short passes that have been Brady's bread-and-butter throughout his career, particularly when vertical patterns are used to occupy the best pass defenders. This is by design, of course, as the point of Cover 3 is to force the offense to beat you by stringing together short gain after short gain rather than with big plays. Brady proved capable of doing so against a Seattle defense with far better personnel two years ago, repeatedly checking down to Edelman and Shane Vereen with ruthless efficiency during a fourth quarter comeback for the ages.

Stay tuned next week, as I'll be taking a look back at the film from the Seattle Super Bowl for a closer look at how to attack their Cover 3. For more immediate reading on the Seattle-style Cover 3, check out this film study piece I wrote prior to that Super Bowl on it's principles and vulnerabilities